Government Control and Limits on Religion Law Review

This is the 11th in a serial of annual reports by Pew Research Center analyzing the extent to which governments and societies around the world impinge on religious behavior and practices. The studies are part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures projection, which analyzes religious alter and its affect on societies around the world.

To measure global restrictions on religion in 2018 – the near contempo year for which information is available – the study rates 198 countries and territories by their levels of government restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving organized religion. The new report is based on the aforementioned 10-signal indexes used in the previous studies.

- The Government Restrictions Index measures government laws, policies and actions that restrict religious beliefs and practices. The GRI comprises 20 measures of restrictions, including efforts by government to ban particular faiths, prohibit conversion, limit preaching or give preferential treatment to 1 or more religious groups.

- The Social Hostilities Index measures acts of religious hostility by private individuals, organizations or groups in lodge. This includes religion-related armed conflict or terrorism, mob or sectarian violence, harassment over attire for religious reasons, or other faith-related intimidation or abuse. The SHI includes 13 measures of social hostilities.

To track these indicators of regime restrictions and social hostilities, researchers combed through more than than a dozen publicly available, widely cited sources of data, including the U.S. State Department'due south annual reports on international religious freedom and almanac reports from the U.Southward. Commission on International Religious Freedom, besides equally reports from a diversity of European and UN bodies and several contained, nongovernmental organizations. (Encounter Methodology for more details on sources used in the written report.)

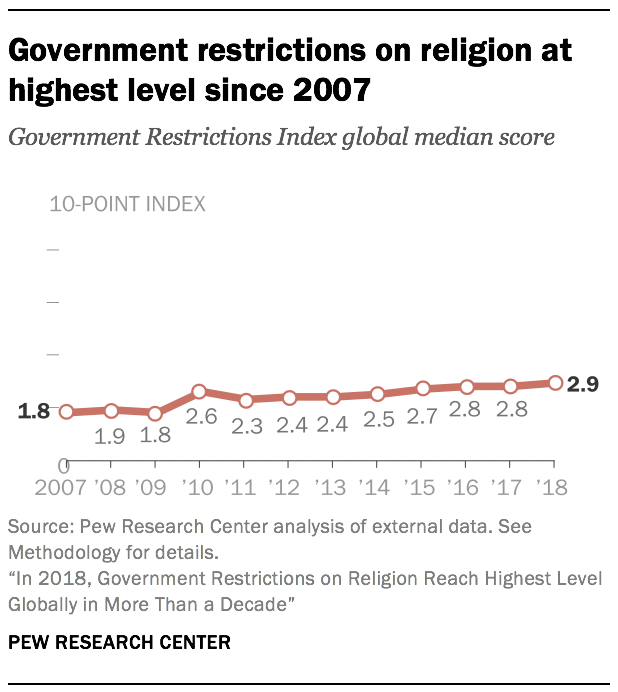

In 2018, the global median level of government restrictions on religion – that is, laws, policies and actions by officials that impinge on religious beliefs and practices – connected to climb, reaching an all-time high since Pew Research Eye began tracking these trends in 2007.

In 2018, the global median level of government restrictions on religion – that is, laws, policies and actions by officials that impinge on religious beliefs and practices – connected to climb, reaching an all-time high since Pew Research Eye began tracking these trends in 2007.

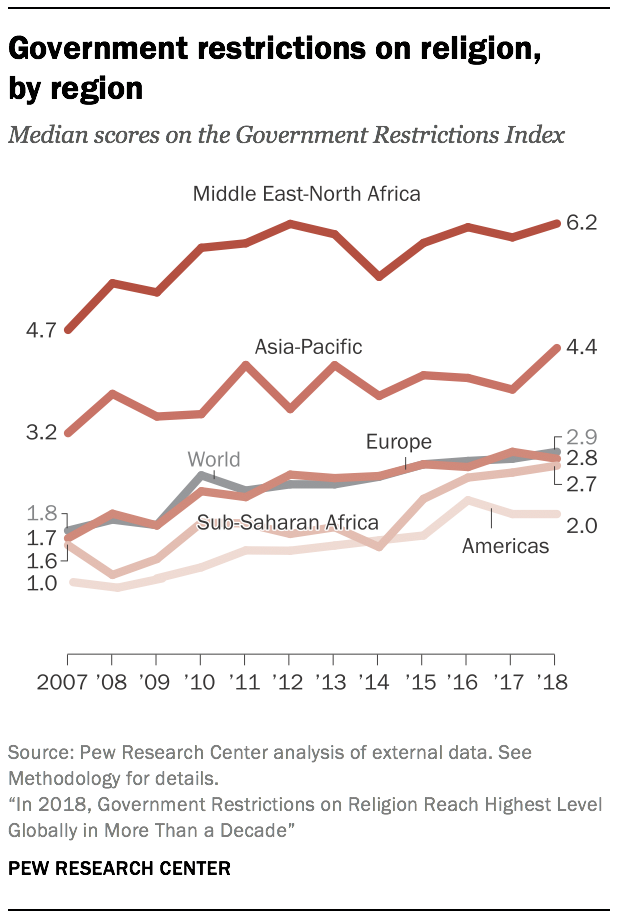

The year-over-year increase from 2017 to 2018 was relatively small, just it contributed to a substantial rise in authorities restrictions on religion over more than a decade. In 2007, the first year of the written report, the global median score on the Authorities Restrictions Index (a ten-point scale based on 20 indicators) was one.viii. Later some fluctuation in the early on years, the median score has risen steadily since 2011 and now stands at 2.nine for 2018, the most recent total year for which information is available.

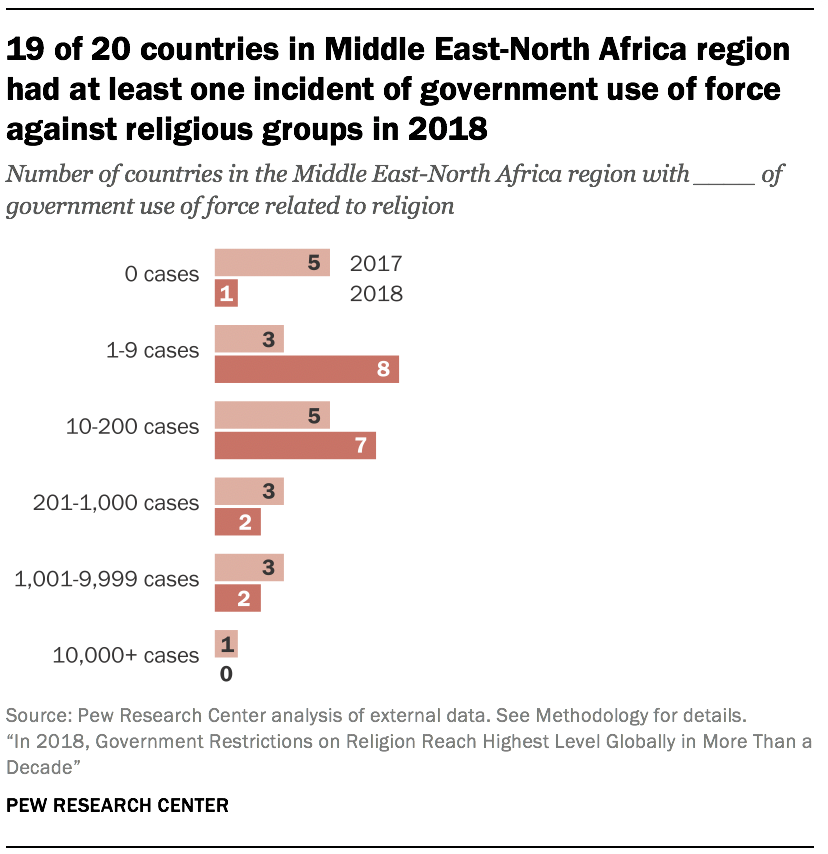

The increase in authorities restrictions reflects a broad variety of events around the world, including a ascent from 2017 to 2018 in the number of governments using strength – such every bit detentions and concrete abuse – to coerce religious groups.

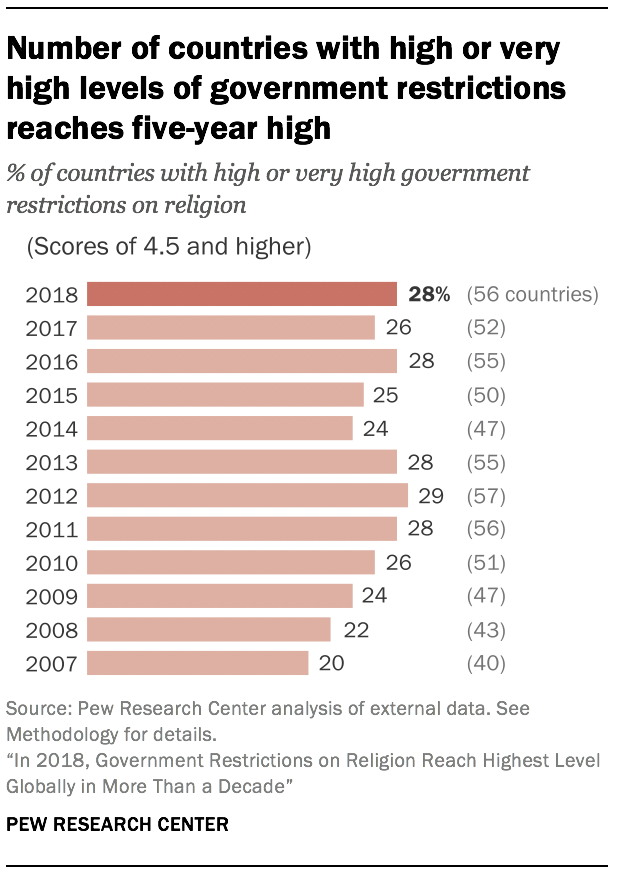

The total number of countries with "high" or "very loftier" levels of government restrictions has been mounting as well. Most recently, that number climbed from 52 countries (26% of the 198 countries and territories included in the study) in 2017 to 56 countries (28%) in 2018. The latest figures are close to the 2012 peak in the top 2 tiers of the Government Restrictions Alphabetize.

The total number of countries with "high" or "very loftier" levels of government restrictions has been mounting as well. Most recently, that number climbed from 52 countries (26% of the 198 countries and territories included in the study) in 2017 to 56 countries (28%) in 2018. The latest figures are close to the 2012 peak in the top 2 tiers of the Government Restrictions Alphabetize.

As of 2018, most of the 56 countries with high or very loftier levels of government restrictions on organized religion are in the Asia-Pacific region (25 countries, or half of all countries in that region) or the Eye Due east-Northward Africa region (18 countries, or 90% of all countries in the region).

Rising government restrictions in the Asia-Pacific region

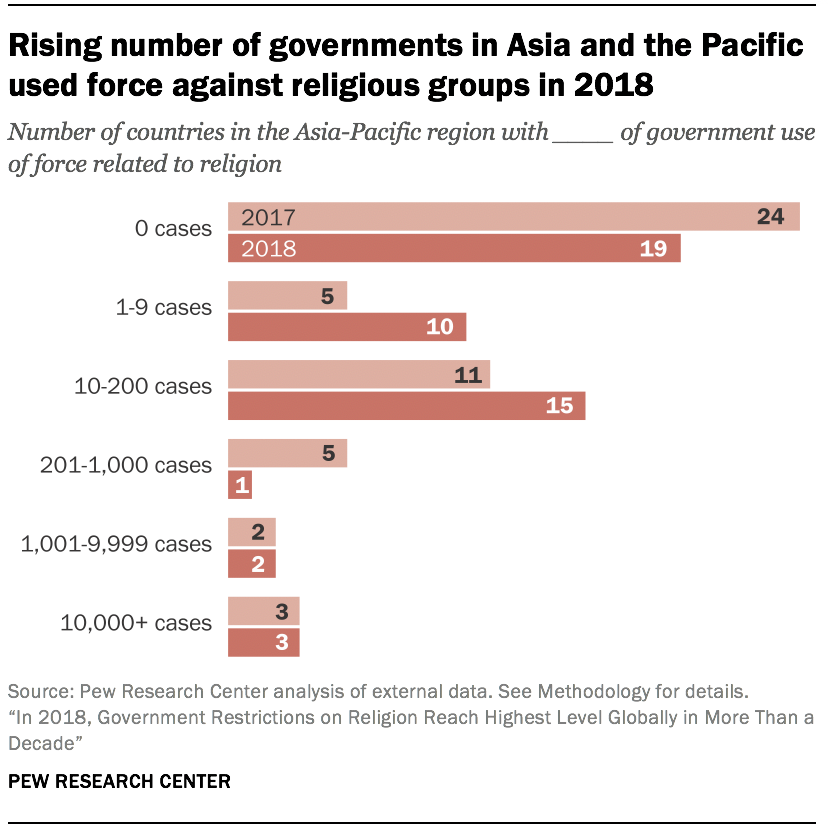

Out of the five regions examined in the study, the Middle East and North Africa continued to have the highest median level of government restrictions in 2018 (6.2 out of x). However, Asia and the Pacific had the largest increase in its median government restrictions score, rising from 3.eight in 2017 to iv.four in 2018, partly because a greater number of governments in the region used force against religious groups, including property damage, detention, displacement, corruption and killings.

In total, 31 out of 50 countries (62%) in Asia and the Pacific experienced government use of strength related to religion, up from 26 countries (52%) in 2017. The increment was concentrated in the category of "low levels" of government use of forcefulness (betwixt ane and 9 incidents during the year). In 2018, 10 Asia-Pacific countries brutal into this category, upwardly from v the previous year. (For a full listing of countries in the Asia-Pacific region, come across Appendix C.)

In total, 31 out of 50 countries (62%) in Asia and the Pacific experienced government use of strength related to religion, up from 26 countries (52%) in 2017. The increment was concentrated in the category of "low levels" of government use of forcefulness (betwixt ane and 9 incidents during the year). In 2018, 10 Asia-Pacific countries brutal into this category, upwardly from v the previous year. (For a full listing of countries in the Asia-Pacific region, come across Appendix C.)

In Armenia, for example, a prominent member of the Baha'i organized religion was detained on religious grounds, co-ordinate to members of the community.ane And in the Philippines, three United Methodist Church missionaries were forced to get out the country or faced problems with visa renewals later on they were involved in investigating human rights violations on a fact-finding mission.two

Just the region also saw several instances of widespread use of government forcefulness against religious groups. In Burma (Myanmar), big-scale deportation of religious minorities continued. During the course of the year, more than fourteen,500 Rohingya Muslims were reported by Human Rights Watch to have fled to neighboring Bangladesh to escape abuses, and at least 4,500 Rohingya were stuck in a edge area known as "no-human being'south state," where they were harassed past Burmese officials trying to get them to cantankerous to Bangladesh.3 In add-on, fighting between the Burmese armed forces and armed ethnic organizations in the states of Kachin and Shan led to the displacement of other religious minorities, generally Christians.4

Meanwhile, in Uzbekistan, it is estimated that at least i,500 Muslim religious prisoners remained in prison on charges of religious extremism or membership in banned groups.v

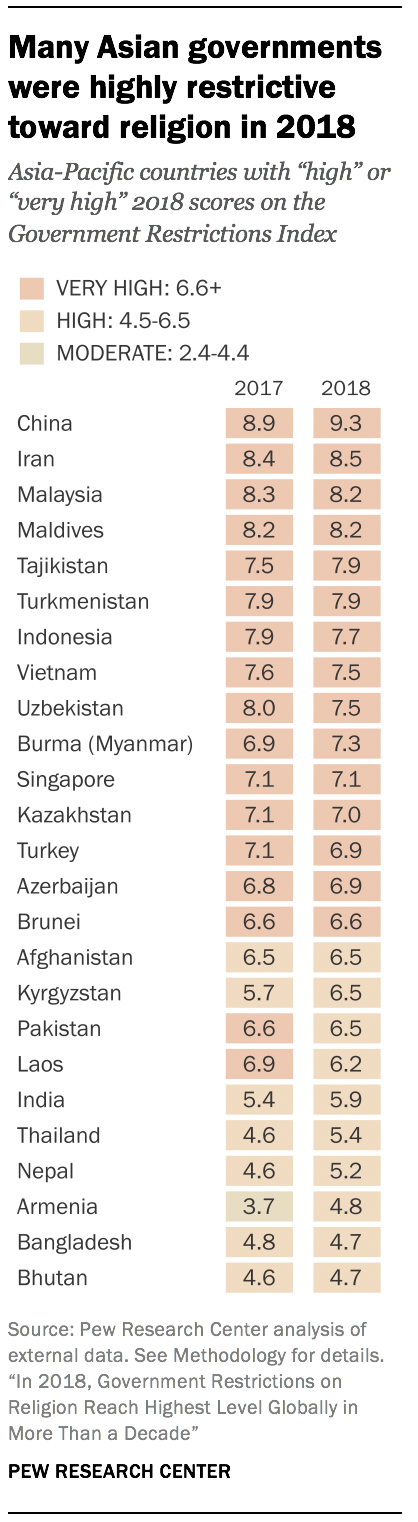

Some countries in the Asia-Pacific region saw all-time highs in their overall government restrictions scores. This includes China, which continued to have the highest score on the Government Restrictions Index (GRI) out of all 198 countries and territories in the written report. China has been near the top of the list of most restrictive governments in each year since the inception of the study, and in 2018 it reached a new peak in its score (9.iii out of 10).

The Chinese government restricts religion in a variety of ways, including banning unabridged religious groups (such every bit the Falun Gong motility and several Christian groups), prohibiting certain religious practices, raiding places of worship and detaining and torturing individuals.half dozen In 2018, the government continued a detention campaign confronting Uighurs, ethnic Kazakhs and other Muslims in Xinjiang province, property at least 800,000 (and perhaps upwards to two million) in detention facilities "designed to erase religious and ethnic identities," according to the U.S. State Section.7

Tajikistan as well stands out with a GRI score of vii.nine, an all-time high for that country. In 2018, the Tajik authorities amended its religion police, increasing control over religious instruction domestically and over those who travel abroad for religious teaching. The amendment likewise requires religious groups to report their activities to regime and requires state approval for appointing imams. Throughout the twelvemonth, the Tajik authorities continued to deny minority religious groups, such equally Jehovah'southward Witnesses, official recognition. In January, Jehovah's Witnesses reported that more than a dozen members were interrogated past police and pressured to renounce their faith.8

While these are examples of countries with "very loftier" government restrictions on religion in Asia and the Pacific, there also are several notable countries in the "high" category that experienced an increment in their scores. India, for instance, reached a new superlative in its GRI score in 2018, scoring five.9 out of 10 on the index, while Thailand likewise experienced an all-time high (5.4).

While these are examples of countries with "very loftier" government restrictions on religion in Asia and the Pacific, there also are several notable countries in the "high" category that experienced an increment in their scores. India, for instance, reached a new superlative in its GRI score in 2018, scoring five.9 out of 10 on the index, while Thailand likewise experienced an all-time high (5.4).

In India, anti-conversion laws affected minority religious groups. For example, in the land of Uttar Pradesh in September, police charged 271 Christians with attempting to convert people past drugging them and "spreading lies virtually Hinduism." Furthermore, throughout the year, politicians made comments targeting religious minorities. In Dec, the Shiv Sena Party, which holds seats in parliament, published an editorial calling for measures such as mandatory family planning for Muslims to limit their population growth. And law enforcement officials were involved in cases against religious minorities: In Jammu and Kashmir, iv police force personnel, among others, were arrested in connection with the kidnapping, rape and killing of an viii-yr-old girl from a nomadic Muslim family, reportedly to button her community out of the expanse.9

In Thailand, as part of broader immigration raids in 2018, the government arrested hundreds of immigrants who allegedly did non have legal status, including religious minorities from other countries who were seeking asylum or refugee status. Amidst the detainees were Christians and Ahmadi Muslims from Pakistan as well as Christian Montagnards from Vietnam. During the yr, Thai authorities besides detained six leading Buddhist monks, a move that the government said was an effort to curb abuse but that some observers called a politically motivated attempt to assert control over temples.ten

Regime restrictions on organized religion in other regions

While Asia and the Pacific had the largest increases in their Government Restrictions Index scores, the Heart E and N Africa nonetheless had the highest median level of government restrictions, with a score of 6.2 on the GRI – upward from 6.0 in 2017, more than than double the global median (2.9), and at its highest indicate since the backwash of the Arab Spring in 2012.

While Asia and the Pacific had the largest increases in their Government Restrictions Index scores, the Heart E and N Africa nonetheless had the highest median level of government restrictions, with a score of 6.2 on the GRI – upward from 6.0 in 2017, more than than double the global median (2.9), and at its highest indicate since the backwash of the Arab Spring in 2012.

As in Asia, the rise in GRI scores in the Middle East and North Africa was partly due to more governments using forcefulness against religious groups. All only ane state in the region had reports of regime use of strength related to religion in 2018, although many were at the lowest level (between one and nine incidents). In Jordan, for example, a media personality and an editor employed at his website were detained and charged with "sectarian incitement and causing religious strife" for posting on Facebook a cartoon of a Turkish chef sprinkling salt at Jesus' Last Supper.11

But regime forcefulness confronting religious groups was much more than widespread in some countries in the region. In Saudi Arabia, for instance, more than 300 Shiite Muslims remained in prison in the land's Eastern Province, where the authorities has arrested more 1,000 Shiites since 2011 in connection with protests for greater rights.12

Aside from Asia-Pacific and the Centre East-North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa was the only other region to experience an increase in its median level of authorities restrictions in 2018 (from 2.6 to ii.vii), reaching a new high following a steady ascent in recent years. While government use of forcefulness confronting religious groups decreased in the region, both harassment of religious groups and physical violence against minority groups went upwards.

Aside from Asia-Pacific and the Centre East-North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa was the only other region to experience an increase in its median level of authorities restrictions in 2018 (from 2.6 to ii.vii), reaching a new high following a steady ascent in recent years. While government use of forcefulness confronting religious groups decreased in the region, both harassment of religious groups and physical violence against minority groups went upwards.

More than eight-in-x countries in the sub-Saharan region (twoscore out of 48) experienced some form of government harassment of religious groups, and 14 countries (29%) had reports of governments using physical coercion against religious minorities. In Mozambique, for example, the government arbitrarily detained men, women and children who appeared to be Muslim in response to violent attacks on civilians and security forces past an insurgent group. According to media and local organizations, the regime response to the attacks was "heavy-handed."13

Europe experienced a pocket-size decline in its median level of government restrictions, falling from 2.nine in 2017 to ii.8 in 2018, although government use of force increased slightly (see Affiliate iii for details). The median level of government restrictions in the Americas, meanwhile, remained stable between 2017 and 2018, as the region connected to experience the lowest levels of government restrictions compared with all other regions.

This is the 11th almanac report in this continuing study, which looks not only at government restrictions on organized religion only besides at social hostilities involving faith – that is, acts of religion-related hostility by private individuals, organizations or groups in social club.

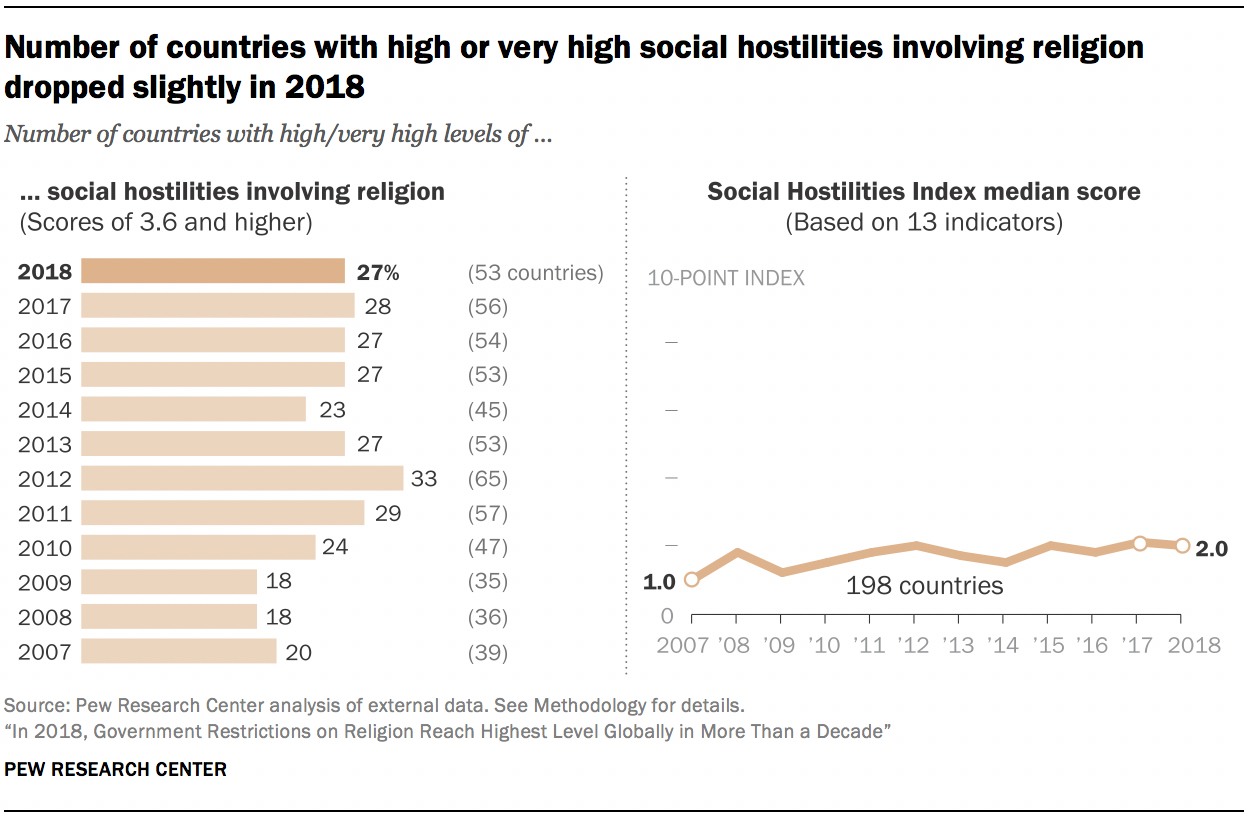

The new analysis finds that globally, social hostilities declined slightly in 2018 after hitting an all-time loftier the prior year. The median score on the Social Hostilities Index (a 10-point scale based on 13 measures of social hostilities involving religion) barbarous from two.one in 2017 to 2.0 in 2018. This pocket-sized turn down was partly due to fewer reports of incidents in which some religious groups (usually of a majority faith in a particular state) attempted to prevent other religious groups (normally of minority faiths) from operating. There also were fewer reports of individuals being assaulted or displaced from their homes for religious expression that goes against the bulk organized religion in a land (see Appendix D for full details).

The number of countries with "high" or "very loftier" levels of social hostilities involving religion also declined slightly from 56 (28% of all 198 countries and territories in the study) to 53 (27%). This includes xvi European countries (36% of all countries in Europe), 14 in the Asia-Pacific region (28% of all Asia-Pacific countries) and 11 in the Middle East and Due north Africa (55% of MENA countries).

Taken together, in 2018, xl% of the world'south countries (fourscore countries overall) had "high" or "very high" levels of overall restrictions on faith — reflecting either government actions or hostile acts by private individuals, organizations or social groups – downward slightly from 42% (83 countries) in 2017. This remains close to the 11-year superlative that was reached in 2012, when 43% (85 countries) had high or very loftier levels of overall restrictions. By this combined measure, equally of 2018, all 20 countries in the Center Due east-North Africa region have high overall restrictions on religion, as practice more than half of Asia-Pacific countries (27 countries, or 54% of the region) and more than a third of countries in Europe (17 countries, 38%).

For full results, encounter Appendix F.

How do restrictions on religion vary by regime blazon?

How the Democracy Index works

The Democracy Alphabetize, compiled by the Economist Intelligence Unit, measures the state of republic in 165 independent countries and ii territories around the earth. The Alphabetize assesses states based on lx questions that broadly comprehend five themes: electoral process and pluralism, ceremonious liberties, the functioning of government, political participation, and political culture. Each state is given a numeric score between

0 and x on the index and is classified into four government types.

• Full Democracies: scores greater than eight

• Flawed Democracies: scores greater than 6, and less than or equal to eight

• Hybrid Regimes: scores greater than 4, and less than or equal to 6

• Authoritarian Regimes: scores less than or equal to 4

In this report, for the first time, Pew Research Eye combined its data on government restrictions and social hostilities involving faith with a classification of regime types, based on the Democracy Alphabetize compiled by the Economist Intelligence Unit of measurement.14 Researchers did this to discern whether there is a link between different models of regime and levels of restrictions on faith – in other words, whether restrictions on organized religion tend to be more or less mutual in countries with full or fractional democracies than in those with authoritarian regimes.15

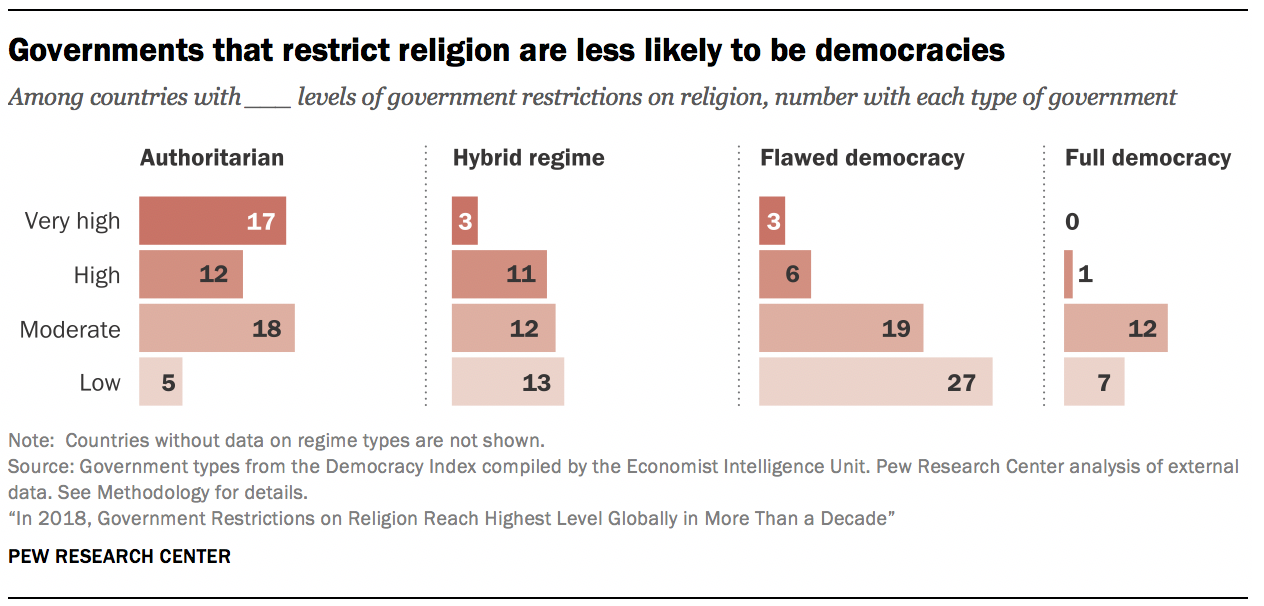

The analysis finds a strong clan between authoritarianism and authorities restrictions on organized religion. While in that location are many exceptions to this pattern, disciplinarian regimes are much more common amongst the countries with very loftier government restrictions on organized religion – roughly two-thirds of these countries (65%) are classified as disciplinarian. Among countries with low authorities restrictions on organized religion, meanwhile, simply vii% are authoritarian.

There is less of a articulate blueprint when it comes to social hostilities involving religion. There are no countries classified past the Economist Intelligence Unit of measurement as full democracies that have very high levels of social hostilities involving religion (just as at that place are no full democracies with very high levels of government restrictions involving faith). At the same fourth dimension, there are many authoritarian countries with low levels of social hostilities involving organized religion, suggesting that in some cases, a authorities may restrict religion through laws and actions past state authorities while limiting religious hostilities amongst its citizens.

When looking at countries with very high government restrictions on religion, Pew Research Centre found that of the 26 countries in this category whose regimes were scored past the EIU on its Democracy Alphabetize in 2018, 17 (65%) were classified every bit authoritarian, three were hybrid regimes (12%) and 3 were flawed democracies (12%). In that location were no countries with very high government restrictions that were full democracies.16 The iii countries with very high government restrictions that were classified as flawed democracies – Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore – all are regionally clustered in Southeast Asia.

Of the 30 countries with high authorities restrictions on religion, there were 12 authoritarian states (40%), xi hybrid regimes (37%) and six flawed democracies (20%), according to the EIU Republic Index. One full democracy, Denmark, also was in this category. In 2018, Denmark fell into the high authorities restrictions category for the commencement time, with its score driven partly by a ban on face coverings, which included Islamic burqas and niqabs, that went into effect that year.17

At the other terminate of the spectrum, amidst the 74 countries with low authorities restrictions, simply 5 were classified as authoritarian (7%), xiii were hybrid regimes (18%), 27 were flawed democracies (36%) and seven were full democracies (9%). The countries with low authorities restrictions on religion that were also classified as authoritarian by the Republic Index are all in sub-Saharan Africa: Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Republic of the Congo, Swaziland and Togo. There was no Democracy Alphabetize nomenclature of authorities type for 22 countries with low government restrictions (for a total list, see Appendix East).

In terms of social hostilities involving religion, the motion picture is more mixed – which makes sense given that social hostilities await at actions by private individuals or social groups and do not direct originate from government actions.

Among the x countries with very loftier levels of social hostilities, in that location were 4 authoritarian states, three hybrid regimes and iii flawed democracies – India, Israel and Sri Lanka. Over again, like countries with very high government restrictions, there were no full democracies with very loftier levels of social hostilities.

Amid the 43 countries with loftier levels of social hostilities, nine were classified equally authoritarian (21%), 14 were hybrid regimes (33%), thirteen were flawed democracies (30%) and five were full democracies (12%).18

The five countries categorized as full democracies with loftier levels of social hostilities are all in Europe – Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United Kingdom – and all had reports of anti-Muslim and anti-Semitic incidents. In Switzerland, for case, Muslim groups reported growing anti-Muslim sentiments due to negative coverage by the media and hostile soapbox on Islam past right-leaning political parties. During the year, for instance, a journalist who had initiated a local ban on face coverings handed out a "Swiss Stop Islam Honor" of most $2,000 USD to iii recipients.19

Among the 81 countries with low levels of social hostilities in 2018, there were 24 with no data on government types (mostly small isle nations the Democracy Alphabetize does not cover). Those with information are well-nigh commonly classified equally flawed democracies (26 countries, or 32% of the 81 countries with depression social hostilities).

Only, strikingly, 17 countries (21%) with low social hostilities involving religion were classified as disciplinarian – including countries like Eritrea and Kazakhstan, which accept very high regime restrictions on organized religion. In addition, several other authoritarian states with very high authorities restrictions on faith – such as Cathay, Iran and Uzbekistan – have only moderate levels of social hostilities involving religion. In these cases, high levels of government control over religion may atomic number 82 to fewer hostilities past nongovernment actors.

The rest of this report looks more closely at other changes in religious restrictions in 2018, including the countries with the near extensive government restrictions or social hostilities and the extent of changes in restrictions on religion since 2017 (Chapter 1); details about the harassment of specific religious groups (Chapter 2); and additional assay on restrictions on religion by region (Chapter 3) and amid the almost populous countries in the world (Chapter 4).

Full results for all countries are available in Appendix F.

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2020/11/10/in-2018-government-restrictions-on-religion-reach-highest-level-globally-in-more-than-a-decade/

0 Response to "Government Control and Limits on Religion Law Review"

Post a Comment